The Book of Jobs Part 2 was originally published in Reglar Wiglar #23.

Welcome to the second installment of my work chronicles. Bonus points if you read the Part 1, which was the first installment of my three-part (but possibly neverending) series concerning all the jobs I’ve had in my life so far. It’s a good place to start, but if you didn’t start there, but are starting here instead, don’t let that prevent you from moving forward or going back.

Part 2 picks up in 1988 and details my slide into the restaurant industry and all the pleasure and pain found therein, but mostly pain. In just a few short years, my career propelled me from simple dishwasherdom to the rock star life of a line cook.

There were a few brief forays into telemarketing as well. Apparently, when I was younger, I could swing through big life changes like an apeman on a vine. Changing schools, jobs, apartments — all within months of each other — that was just how I rolled.

Also ahead, my further hash-slinging adventures in more bars and bistros, plus a long stint in the newspaper classified ad business, a very short journey through ad agency hell, unemployment, an untriumphant return to food service, even more food service, and a job doing art installation that nobody could have predicted.

What will be the exciting conclusion to all this? Will it be over? Will I finally hang up my apron and become self-employed? Inquiring minds want to know. I want to know. Until then, for now, here is Reglar Wiglar #23 for your reading enjoyment. Once again, I hope you get a good swift kick out of it.

The Dishwasher

Nineteen eighty-eight. It was the summer of Hair Metal. The summer of “Nuthin’ But A Good Time” and “Every Rose Has Its Thorns.” “Sweet Child of Mine” was blasting out of the open windows of every Camaro and Trans Am in town. Every time I heard “Pour Some Sugar on Me” I wanted to vomit and every time I heard “Kiss Me Deadly,” I wanted to cry (it ain’t no big thing).

The summer of 1988 I spent in the bowels of the Eagle Ridge Inn at the Galena Territory. I was a dishwasher, it’s true. The Territory was, and still is as far as I know, a gigantic, sprawling private development covering thousands of rolling acres of resort-y splendor, including two golf courses, a man-made lake, and a large, seasonal population of wealthy Chicagoans.

Dishwashing Crüe

The Eagle Ridge Inn was a hotel and restaurant complex where two restaurants and a bar were connected by one big kitchen. Each restaurant had its own line and dishwashing station but shared a common prep area and a three-compartment sink for pots and pans.

A single window connected to a separate bar area allowing for dirty glasses to be passed back to the dish area off the main dining room. As a part of a teen-aged dishwashing crew of five or six, I washed dishes in that kitchen for four months, moving from one dish station to the next as need dictated.

Unlike almost every other dishwasher at the Eagle Ridge Inn, and most of the general population of rural northwest Illinois at that time, I was not a headbanger. I hated cheese metal as much as I loved punk rock. There was no bandana on any part of my body and no mullet flap rested comfortably on the nape of my neck. I was definitely in the minority in that respect, but there I was among them, nonetheless.

There were some lazy dudes on that dish crew, some of the laziest I have ever encountered before or since. When I could, I volunteered to work downstairs in the banquet kitchen. Even though I had to wash all the dishes by myself: glassware, flatware, and all the side plates, dessert plates, soup bowls, and serving containers for parties as big as two hundred people — and sometimes until one or two in the morning! — I preferred it to working with that slacker crew upstairs in the main kitchen.

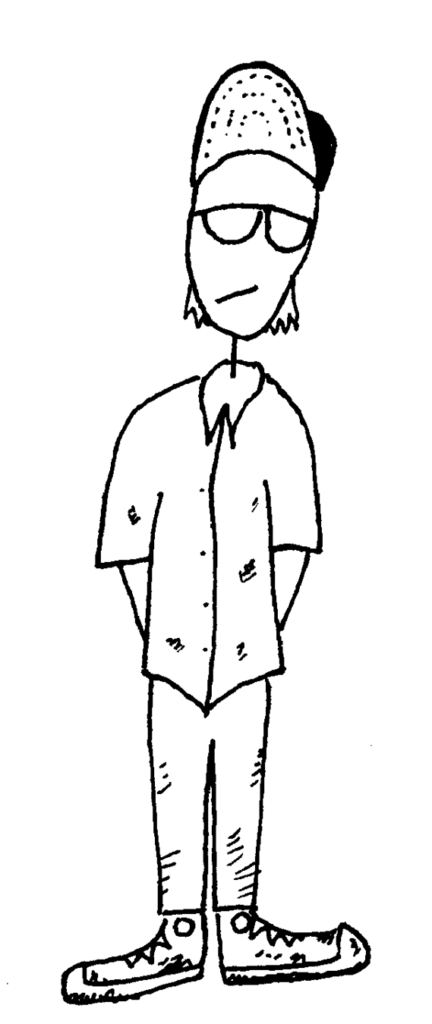

A Man in Uniform

Four months I wore the dishwasher’s uniform, which consisted of white pants and a white button-down short-sleeved shirt. I guess technically it was a snap-down shirt (which I wore snapped up to the top with the bill of my baseball cap flipped up in the style popularized by the West Coast gangstas of the time) and accessorized by my soon-to-be-destroyed-by-kitchen-scum and completely-unsafe-for- any-commercial-kitchen-floor Chuck Taylors.

There were some characters in that kitchen too. A less kind individual might have called them freaks. There was Flash, who every day wore a different colored bandana tied around his head. Flash chose the color according to his mood that day. “If you see me wearing a red bandana, don’t fuck with me.” The Department of Homeland Security has employed a similar color-coded warning system. The fact that Flash’s headwear incorporated any sort of warning system at all, regardless of the color, was enough for me to steer clear of him altogether.

Then there was Popeye, a compact and wiry, bearded biker who was more cross-eyed than what you might call popeyed.

Popeye

Popeye was a lewd, crude, pot-smoking, hard-drinking dude. And talk about sexual harassment! The waitresses (they were all female in the main dining room) were subjected to his many colorful, shouted refrains throughout the course of every dinner service, “I need a blow job!” being one of the more popular ones. “Just like Mom used to buy” was another one Popeye used endlessly when plating up a grilled duck or a filet of beef. It’s a line I stole from him and have used many times in my cooking career. Very seldom does it fail to get a laugh.

Almost every teenager who has lived in Jo Davies County has worked at the Galena Territory at some point, either as housekeepers, dishwashers, bussers, bellhops, or attendants at one of the golf courses.

I don’t know why I chose the grimiest job available, but dishwashing has a certain appeal. It’s pretty straightforward. There are no gray areas. You take the dirty dishes and you wash them, then you put them away. Repeat until quittin’ time. You mostly work alone and everyone who isn’t a dishwasher pities your plight. So, as much as it did suck to get off work at midnight (or later), soaked to the bone and covered in a thin layer of grease, and to bust ass six days a week, it wasn’t too much, and it was only temporary. The job ended when I left for Chicago and college. It was time to leave the townies to their town and bust out of the sticks never to return — or at least not for nine months.

The Law Clerk

Even though I was paid a pathetic minimum wage for washing dishes ($3.35), I worked a lot of overtime and saved a lot of money that summer. So when I got to Chicago and to DePaul University, I wasn’t in a big hurry to find a job. However, fate intervened like a kick to the huevos, and a little boo-boo at the financial aid office had me writing a check for almost my entire savings. It was an accounting error that wouldn’t be corrected until I received a refund check at the end of the academic year—eight months away! I had to get a job.

After a few weeks of fruitless employment searches, I became a law clerk. I had connections. My aunt was a lawyer and had a private practice downtown in the Monodnack Building. The job required just a few hours in the afternoons on weekdays, three or four days a week. I can’t remember what it paid, but maybe as much as five or six bucks an hour, plus a monthly CTA pass.

Coming as I did from a town of roughly four thousand people to a city of roughly four million, and getting to wander around beneath the towering office buildings of the Loop, picking up and delivering various legal documents, was pretty cool. It really was a cake job too and it gave me a little extra beer drinking money. And that’s where it all went too. Milwaukee’s best got the best of my paycheck every week (LOL?).

On the Line

When my freshman year ended, I was able to get my refund for the tuition overpayment, so at the beginning of the summer of 1989, it was back to the sticks for three months of rest and relaxation. Having a little cash on hand, I was in no hurry to find another job in Galena. I was content to play Frisbee, drink beer and hang out, but with some “encouragement” from the Old Man I started what was a brief job search.

I figured I would avoid going back to the dish pit, so I started looking for a cooking job in town. My prep experience as a dishwasher could take me to the next culinary level. I applied at the historic DeSoto Hotel in downtown Galena (Lincoln once gave a speech from the balcony of the DeSoto, by the way).

The Chef at the hotel must have called the Executive Chef at Eagle Ridge Inn for a reference because I never heard from the DeSoto Hotel but I got a call from my Bill Wilson telling me he had heard that I had applied for work in town. Bill was small, thin, with an even thinner mustache and slicked-back hair. He chain-smoked Camel filterless cigarettes which was impressive to me at the time, for whatever reason. I felt like I was busted by a jealous girlfriend and forced to return to a bad relationship.

Line Cook

I was offered a job as a line cook, covering for a guy who had been in a motorcycle accident. I could fill several pages with the kitchen exploits that occurred during that summer, including the night when a completely shit-faced Popeye (who was still gainfully employed) showed up for work one Sunday night shitfaced only to continue drinking the pitchers of beer he made me request from the bar for “beer-battered shrimp” which, incidentally, was not on the menu.

It was an epic ordeal that saw Popeye quit several times only to be coaxed back by a desperate waitstaff.

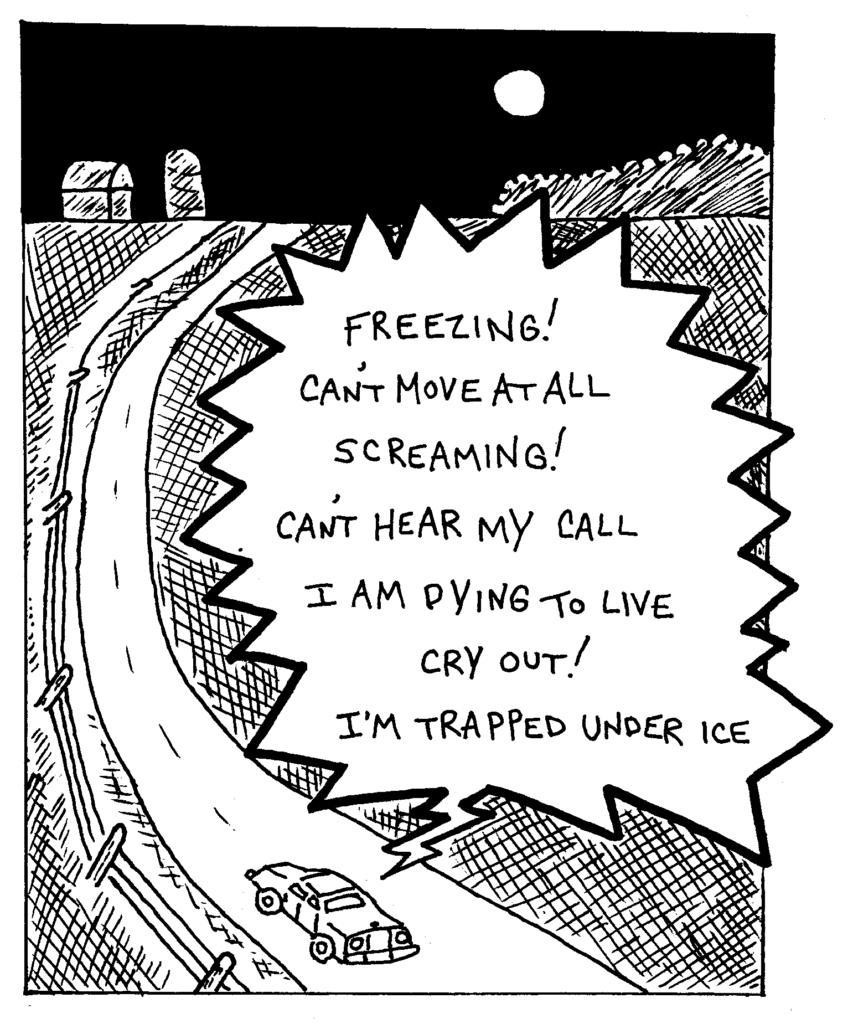

It was after nights like these while driving home listening to Metallica’s Ride the Lightning on my boom box, that I would get an almost uncontrollable urge to drive my Dodge Diplomat right off the road and into a ditch. This job was only for a three-month stint, however, and by not driving off the road at high speed into a ditch, I took another step into culinary life.

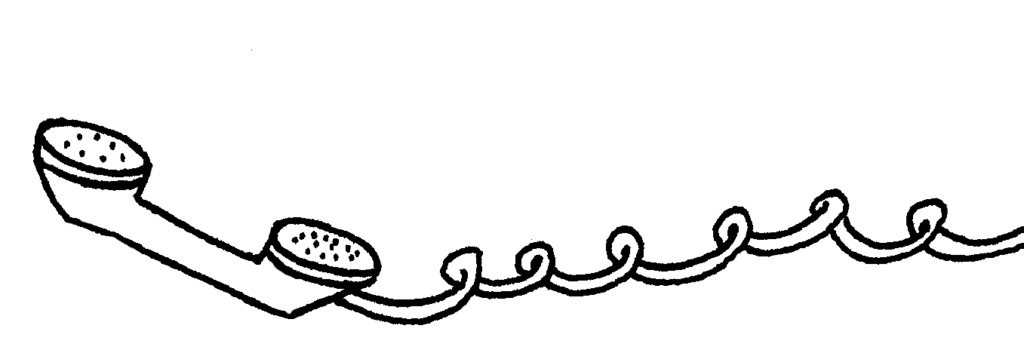

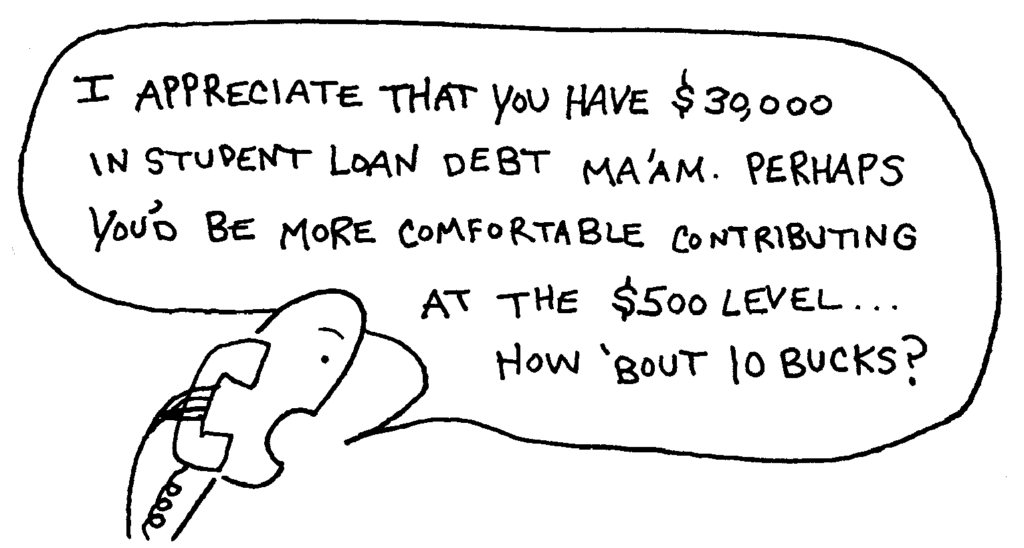

Phonathon

Phonathon was a job that involved phones. I hope that’s as clear today as it was then. The gig was raising money for DePaul University by calling alumni, their parents, and anybody else who had ever set foot on campus, however brief their visit. It paid six bucks an hour, which was unheard of at the time, a good wage. The shifts were only three and a half hours, Monday through Tuesday, with the occasional Sunday afternoon. The call center was on campus so it was very close to where I lived in a shitty little dorm called Corcoran Hall. I would work on and off at Phonathon for several years, even after I transferred out of DePaul, because, well, my boss let me. (Thanks Beth!)

This was a cut-and-dried telemarketing job at its core, but in 1989, people hadn’t quite been pushed to their breaking point on unsolicited phone calls yet. No-call lists didn’t exist yet, although plenty of people asked both politely and impolitely to be taken off our list. Most people were receptive to receiving contact from their old alma mater, even if they didn’t fork over any cash.

We did have a script to follow with various levels, or “asks”, to get through starting at the $1,000 President’s Club or Circle or some such thing. I actually got one of those pledges once, but I don’t recall if they actually mailed in the payment. We also got bonuses and incentives. I got a $100 bonus at one point and spent the entire sum on records which made me feel pretty good. That feeling was very fleeting.

The 3 Penny

At the end of my sophomore year, I decided to stay in Chicago, never to return to the Eagle Ridge Inn of summers’ past. In December of the previous year, a friend from the dorm and I found a two-bedroom apartment a few blocks south of campus in Lincoln Park. The rent was $485 per month. Amazingly cheap even in 1990. It was tiny, of course, hot water and adequate heat were rare and it was located on the second floor scant inches from the Armitage el stop and two el lines, what was then known as the Ravenswood and Howard (Brown and Red lines in modern times).

Tired by this point of doing phone solicitation work, I got a job at a movie theater in the neighborhood. This particular gig lasted two days, roughly ten hours overall.

The theater was a small independent art house on Lincoln Avenue, run by a middle-aged married couple. I had quite a few friends who had worked at this place for various lengths of time so I got hired pretty easily, even though I don’t think they were necessarily hiring at the time.

Reel too Real

Washing the projectionist’s car in the alley behind the theater was one of the tasks I performed during my brief career in the movie business. I was also asked to pull weeds from the alley that ran along the side and in back of the building. Yes, I pulled weeds from an alley — a dirty, smelly alley that was no doubt full of urine and vomit and the scene of many atrocities (it was located directly across the street from the alley where Dillinger was shot).

My tasks inside the theater were ripping a few tickets here and there and cruising through the theaters on the lookout for masturbators, which is more along the lines of what you would expect of a movie theater usher. I did not encounter any pervs. For the most part, the job was incredibly boring. So boring, in fact, that after working just two days, I did not for ask for more hours, which they really didn’t have to offer anyway. It was summer and I was looking for a full-time job, which I found, and that brings us to the next chapter.

Life on the Mississippi

Groucho Marx once said he wouldn’t want to belong to any club that would have him as a member. Likewise, I don’t really know if I trust a company that would hire me to work for them. Especially if they were to hire me on the spot like the riverboat company I worked for in the summer of 1990.

I found out about the job from a good friend from Galena, a fellow resort worker, a bellman, who had gotten a job on the boat as a porter. This particular enterprise was in possession of two ancient paddle boats which they still sent up and down the Mississippi and Ohio rivers laden with geriatric retirees. I mailed them my application to work as a cook in the kitchen on their Delta Queen riverboat and they must have considered my credentials for all of five minutes because I received a plane ticket by FedEx just a few days later.

Reporting for Duty

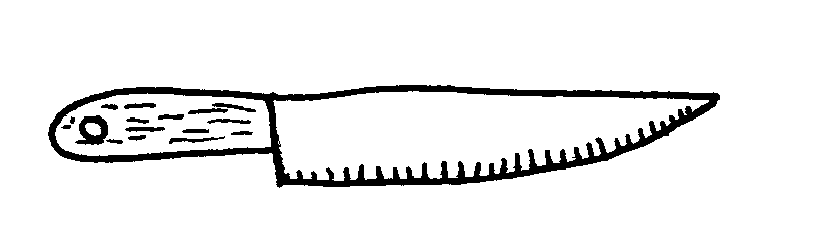

I was hired as a First Cook and was to report for duty before the week was out. The only thing that I was required to bring was my own set of, presumably professional, kitchen knives. Instead, I flew to New Orleans with the shittiest collection of knives Sears ever sold. As soon as I stepped off the plane and got that first blast of heavy, humid, and oppressive Louisiana air, I had an inkling that this gig might suck. I could not fathom, however, just how much it would suck.

After working a half shift in the kitchen that first afternoon, I was told to report back at 2 a.m. for my regular shift which was 2 a.m. to 2 p.m. If that seems early it’s because it is, but the dock-loading crew had to be fed before they started their horrible day and that was well before the sun was up.

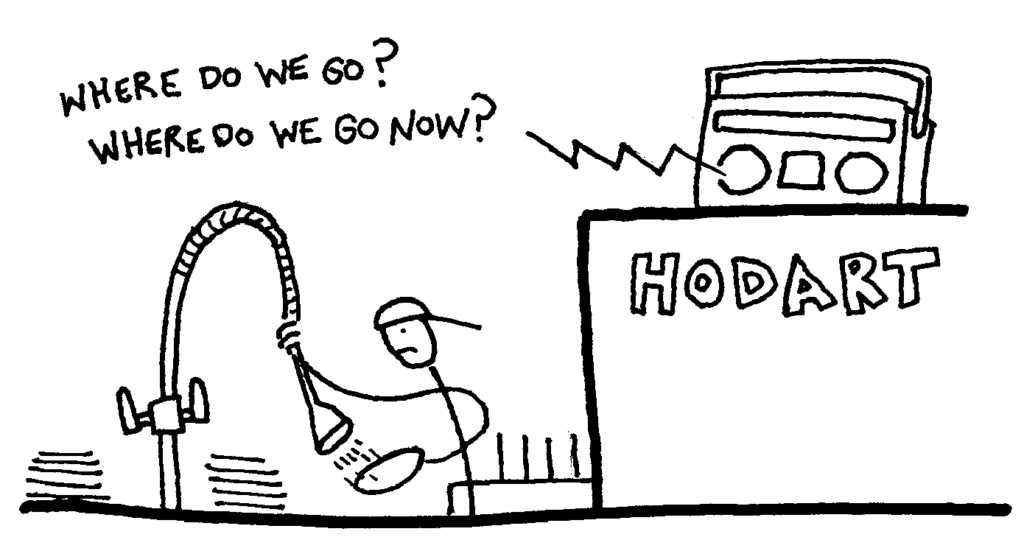

Egg Shift

It quickly became apparent that, with the exception of the kitchen manager, I was the only dude (they were no women in the galley) who was from outside of Louisiana. My small town Yankee butt had a difficult time deciphering the dialect of the Deep South, but the language barrier was just one of the challenges I had to overcome on the fly. It didn’t help that the waiters didn’t submit their orders in writing, but simply called them out.

The menu was not complicated. It was basically eggs, bacon, and French toast, but I have the kind of brain that needs to visualize for comprehension and that includes seeing orders written on a ticket and not yelled at me in a steady stream.

My new grind was to continue on like this for twelve hours on, twelve hours off, seven days a week for six weeks straight. There

would be two weeks off after that and then another six weeks on. The pay was fifty dollars a day plus “room and board.” The “room” was a tiny, hot, and humid cell with bunk beds located in the bowels of the boat. The “board” was all the eggs I could eat.

After four days of what I could only guess was the single worst job in the world, I was presented with an easy out.

Read “Riverboat Gamble” excerpt from Gray Flag #3.

Praying to God

My predecessor, who had wisely bailed a week or two previously, was scheduled to have his two weeks off just four days after I started. I was basically looking at a two-week vacation after only four days, and they were footing the bill for the plane ticket back to Chicago. I had literally prayed to some god, probably the Christian one, and begged for a way to be taken off that boat and had even contemplated jumping ship in Baton Rouge, but I didn’t know if there were alligators in the Mississippi or not. There was a whole lot I didn’t know about everything, actually and Google wasn’t around to help me.

But now as my bad, then good, misfortune would have it, I didn’t have to worry about any of that. The schedule that was already in place dictated that I was to be flown back to Chicago for two weeks, after which I would be sent a plane ticket to meet the boat in Cincinnati for a six-week trip up the Ohio River to Pittsburgh then back down to New Orleans. Less than a year later I would make it back to New Orleans, ironically enough by way of Cincinnati, but I did not return to the Delta Queen.

NOTE: You read more about my life on the Mississippi in Gray Flag #1 available from RoosterCow Press.

North Side Pimp

After returning to Chicago, I was what you might call flat busted, having only made about $200 the previous two weeks ($50 going to whatever union it was I had to join on the boat). I lived off Corn King hot dogs and bologna as I hit the pavement, again with the weekly Reader classifieds in hand. During this time I was also reading George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London, which will cheer you up if you ever think you have it bad in the food service industry.

According to an ad, there was a bar on Halsted Street just a few blocks from my apartment that was looking for a short-order cook. When I stopped in the bartender informed me that the position had been filled, but, they said, the owner had just opened a new place in Wicker Park and they were looking for line cooks. So I jumped on the #72 bus heading west.

Wicker Park in 1990 was much different than present-day Wicker Park. Very much different, in fact. Prostitutes and crack houses were not uncommon sights back in the day and it always seemed like something was getting ready to pop off at any given moment. Some of those first new businesses that went in after the artists and weirdos staked claim likewise took a pretty big risk decades before the banks and boutiques felt it safe to do so. You could call them pioneers in a sense, but that would be forgetting that people already lived there — people who had no idea their noisy, bustling, gritty, crime-y neighborhood had so much potential for urban chic.

“Pimp!”

Budding gentrification aside, I finished the summer up at the North Side Tavern working with Leroy (aka “June Bug”), Papa Lee, L.L (yes, that stands for Ladies Love) Alex, Winny, and a dude who wasn’t there but a day or two after I started, but who gave me one of the best lines since Popeye when he told me he was so happy when he get off work that he ran home.

In the kitchen I was known by a few aliases all invented by L.L. I was known alternately as “North Side Pimp,” “Billy Clyde,” or the more formal, “Billy Clyde Blue-Eyed Pimp” and sometimes simply “Pimp!” You see, unbeknownst to me at the time, Billy Clyde Tuggle was a pimp on the soap opera All My Children back in the 1970s and ‘80s. You see, I was very obviously not a pimp, therefore the comic irony of such a label was hard to escape.

Space constraints prevent me from going into too much detail about this particular job. It was an eventful four months to be sure and I worked six days a week with plenty of split shifts thrown in (10 a.m. to 2 p.m. and 4 p.m. to 11 p.m.) which required four bus rides per day. I was starting at a new school in the fall and the job required too much time and the commute became too much as well. I quit that September.

NOTE: You read more about my life on the Mississippi in Gray Flag #1 available from RoosterCow Press.

Suffering for Art

Even though I was no longer a DePaul student, in the fall of 1990 I went back to Phonathon for the third or fourth, but definitely final time. I worked the phones through the fall and winter with a new group of incoming students, so young and eager to raise money for their new school.

I felt weird raising money for a school where I was no longer a student so, capitalizing on my experience as a telemarketer, I was able to land a job at the Art Institute of Chicago. The work was very similar. Similar script, similar shifts, similar pay. The only difference was, instead of alums I was bothering former museum subscribers. The building was not on the museum campus but down the street on Monroe, or maybe Madison, but probably Monroe.

I remember having to crawl out the window in the men’s bathroom for cigarette breaks on the fire escape and that the elevator in the building still employed a real live elevator operator, which was so old school that it was new to me. At any rate, by this point I was so sick of the telemarketing thing that I didn’t last long, maybe three or four months. One day I decided that I just couldn’t do it anymore, so I didn’t.

The Ugly Bar

After the last telemarketing gig fizzled, leaving me unemployed for three or four or five weeks, I was beginning to get a little desperate. I had to start selling off my record collection to keep myself in rice and beans. Another ad in the Reader lead me to another restaurant in need of a cook.

The establishment in question, Ugly Bar, consisted of a rather small bar with an outdoor patio that was maybe twice the size of the interior. It was located up the street from the two-and-a-half-bedroom apartment on Lincoln Avenue that I shared with four other twenty-year-old dudes. (Imagine the cleanliness and good hygiene that was routinely observed at this temple of sobriety.) The owner was a cocky frat boy-type in his mid-to-late twenties and he hired me on the spot (bad sign) and told me to come back the next night to train.

Blaizy

Returning the next night, the owner walked me back to the kitchen to introduce me to the kitchen manager, Blaise. That’s funny, I thought to myself, I worked with this really lazy guy named Blaise at a movie theater a few months back. He was eventually fired, just as he had been kicked out of my dorm, then school (and rumor had it, the US Army) prior to that. The owner (whose name has been lost to history) then pulled the curtain back (yes, curtain) on the kitchen to reveal a tiny room outfitted with a pizza oven, refrigerator, sink and an ex-Army, ex-Dorm, ex-student, ex-movie theater worker, and current kitchen manager named Blaise. This was the perfect recipe for the disaster that followed.

The kitchen that Blaise “managed” wasn’t much bigger than a walk-in closet, or the room I was living in at the time, and the crew that Blaise managed apparently consisted of me. There were no other cooks and no dishwasher. It was the most disorganized mess of a kitchen I had ever seen in my life up to that point, which wasn’t many, but still. My fridge at home with four roommates was cleaner and more organized, and that’s saying something because our fridge was real messed up.

Winging It

Blaise was a far worse manager than he was a theater usher. I learned absolutely nothing from him during that night of training. When I returned the next night to work solo, I had no idea how to make anything on the menu. I made pizza dough somewhat successfully. I improvised. Winged it. Not only was I the cook but I was also the dishwasher and, as I wouldn’t find out until much later that night, I was also the busboy.

I discovered that fact well after midnight when a server tipped me off that there were several completely full bus tubs out on the patio that I had to retrieve and wash the contents of. With no dishwashing machine, I did so by hand and then cleaned the kitchen, which didn’t take long. By the time I got home at three o’clock that morning I was as exhausted as I can ever recall being. I was too tired to even drink a beer and that ain’t right.

After working Friday and Saturday nights, I returned on Sunday to quit and ended up walking in on an employee meeting that I knew nothing about and that Blaise insisted he informed me of. I left immediately, walked home, called the bar, and quit that way. This horribly run business closed just a few months later and I was happy to hear it. It usually takes shitty places like that much longer to close down. I will give the owner credit, despite being an over-confident, spoiled and clueless yuppie douchebag, he also gave up easily and thereby did the neighborhood a huge favor. I think a hair salon took over that space next.

Out of the frying pan…

Fugazzios

A Help Wanted sign permanently displayed in the window of any business should be regarded as a bad omen — a big, glaring red flag. It literally translates to “This Place Sucks, Run Away NOW!”, but after the Ugly Bar incident, I was completely demoralized and in a state of perpetual brokedness.

So, after passing by the neighborhood Italian fast-food joint, Fazzio’s, several dozen times, I eventually broke down, went in, and asked for an application. I was hired immediately, of course, and started that week on the day shift working 9-4. I worked ten or so days in a row and was on a six-day-per-week schedule after that. It was a no-brainer gig, I mean, it was fast food.

You had your Italian beef, your Italian sausage, your Italian meatball sandwiches, subs, fries, mozzarella sticks, fried mushrooms, all that crap. After working on the line and washing dishes in a few full-service restaurants, this work was a breeze. Ah, but there was a catch.

Funky Boss

The owner was a certified nut job with a Napoleon complex, a short temper, and all the patience and understanding of a four-year-old. We’ll call him Mike. Mike was an Italian-American transplanted from New Jersey. He allegedly lost a ton of money in the stock market crash in ‘87. He supposedly bought the restaurant because it was a cash business and I’m assuming he thought that the cash would be earned fast and easy.

Even though he visibly hated it, Mike was there serving the public every day Monday through Sunday. What made him so perfect as the public face of the restaurant was that he had absolutely no people skills whatsoever.

In fact, he could in no way hide or disguise his disdain for his customers. His view that everybody other than himself was a complete idiot extended to his employees as well. To be fair, he did employ a fair number of idiots. I would not have lasted as long as I did (three years!) had I not made the move to the night shift, which had me arriving each day just as Mike was leaving. Mike actually liked me, I guess. At the very least he found me not too stupid enough.

Don’t Let the Revolving Door Hit Ya

I never called in sick or asked for time off and I generally made it to work on time, although sometimes with the type of intense hangover only a twenty-one-year-old can create for themselves. Eventually, entirely by default, I was made an assistant manager, then manager. Even after I quit I returned to work part-time for a few months here and there when I needed money. I have hundreds of stories and humorous anecdotes about this restaurant and the employees who came through its revolving door, but that would take an entire issue unto itself.

How was I able to work with such a miserable human being for such a long time is a question I’ve asked myself. It’s all about taking what could be perceived as a really shitty job and making it suit your purposes.

For me, I eventually got promoted with a pay raise and health insurance. I did not have to work directly with Funky Boss, usually ever. I got free food, it was a fifteen-minute walk from my apartment and I had a schedule that allowed me to finish college while working part- or full-time, as my current schedule allowed. And I could do that job in my sleep. When I just couldn’t stomach the place any longer, I put in my two weeks, didn’t burn the bridge, and always had a place to go back to. All I had to do in return was put up with a whole lot of bullshit. No big deal. That’s what six packs are for.

Spike Lemon Ice

But most importantly, that place was completely different at night. The night crew ran it and we didn’t steal or drink on the job. Well, we did spike the lemon ice one time, but that was because we were forced to work on the Fourth of July. The point is, we had fun. Too much fun, probably. We were experts at playing the dozens and took “Your Mama” jokes to new heights, exploring new territory and experimental formats that would reach surreal, even esoteric levels, only to bring it all back down to street level again.

We ate “beef buddies” and mozz sticks whenever we wanted to, and we often went out drinking after work. It was that camaraderie that exists in the restaurant industry that allows you to forget you have such a shitty job, are covered in grease, and still broke most of the time. Some of you know what I’m talkin’ about. Hooyah! It was also when I started publishing the zine you are reading right now.

NOTE: You read more about my life on the Mississippi in Gray Flag #2 available from RoosterCow Press.

Read the Next Chapter of Book of Jobs

Read the Book of Jobs Part 3.