The Book of Jobs details my long and winding employment history. From my early days performing household chores to the years spent in the food service trenches, this is a near-complete examination of every job I’ve ever had.

This three-part series was published in the Reglar Wiglar zine. Part 1 appeared in Reglar Wiglar #22.

So it begins…

Although I have no desire to learn any statistics or do any real “research” on the subject of “work in America,” I would guess that most people work or have held down a job or two in their lives.

I would also guess—and again, no research has gone into this—that most people work long and hard most of their lives, and the rewards are trifling.

At least that has been my experience.

The old adage that we were fed in our formative years concerning the ‘doing of what you love’ has proven to be a crock of steaming, bubbling bullshit, and yet despite this lie, we still must toil at our labors.

But has it really been that bad? I mean really?

Yes. Yes, it has, but the silver lining to this dark and stormy cloud is that I can retire in twenty-five or thirty years… but probably not.

The Book of Jobs

There will certainly be no social security to look forward to. I have no 401(k) plan or pension or — what’s a pension anyway? Don’t know, don’t have one, but my point is this: I will likely be working to the grave and will probably be asked to dig out a few shovelfuls of dirt since I’m going down there anyway.

In spite of this sobering reality, I have expended a lot of time and energy trying to come up with that one idea — that brilliant revenue-generating cash cow of a plan that will keep me in the black for the rest of my life. It just hasn’t happened yet.

As I mentioned above, my research on the subject of work has been limited to my own personal experiences and my reflections on jobs and how they suck.

Thinking about all the jobs I’ve had in my life, I don’t know if it’s a lot, not a lot, or right there at average. I’ve held some jobs for a few years, some for just a few weeks and some for only a few days — hours really, but I’ve never been fired from any of them.

So let’s begin at the beginning then shall we?

Weekly Allowance

They weren’t called “chores” in my house. That word is a little too Little House on the Prairie for my tastes anyway. A chore to me is churning butter or milking a goat or reading William Faulkner.

I did have a few responsibilities in those early grade school years that would fall into the chore category, however. I don’t recall what those responsibilities were, but I remember getting paid fifty cents per week to perform them. That seems like a pretty paltry sum. Of course, this was in nineteen-seventy’s money, so yes, it was a pretty paltry sum. Inflation probably ate up a third of it too (thanks Jimmy Carter!).

Even so, with Star Wars cards selling for fifteen cents a pack and Hot Wheels ringing up at about forty-nine cents per axle, I could afford a few luxuries.

A few years later, when I was old enough to actually do some form of physical labor (haul firewood, take out the trash, wash dishes, i.e. “do the chores”), I think I was pulling in about two fifty per week.

At the time, this was enough dough to pay for my weekly bowling dues at Rusty’s which was a combination bowling alley and Chinese restaurant. (Yes, it was a bowling alley and a Chinese restaurant.) I never became a proficient bowler and Rusty’s has since burned to a cinder which has no significance here except as a side note.

Space Invaders

Somehow I was able to survive week-to-week on two bucks and change. That is until Space Invaders hit town. It was then that I became a video game addict, spending those beautiful, round and ridged quarters as fast as I could earn them—sometimes begging advances on next week’s pay only to squander it all in a matter of minutes at Maggie’s Pool Hall.

And the real tragedy is that I could never even clear the first level of that stupid, stupid game.

Anyway, I can kind of remember—maybe about junior high—my pay doubling to about five bucks a week. I think at about this time my sister and I were both required to cook dinner for the family (of four) one night each week. Not only that, we had to plan the meal ahead of time, write down the ingredients we would need, find them in the grocery aisles when we went shopping, prepare the food, set the table, clear the table, do the dishes and sweep the floor. Immigrant labor, really. Most restaurants run on this model.

Quite a deal for my parents, but they did have to endure more tuna casseroles at my sister’s hands than is possible to count. I made tacos a lot: easy, tasty, multicultural.

As a side note, it should be mentioned that all of the jobs highlighted in this issue took place in Galena, IL.

The Paper Route

I guess my first job where the source of income came from outside the family was when I delivered newspapers for the Telegraph Herald published in Dubuque, Iowa. It was a job I truly hated—a good primer for the future.

I was thirteen. I had subbed for friends’ routes before. It’s a pretty easy gig if you’re only doing it for a day or two, a week at the most, but when you are responsible for getting people their papers every day, rain or shine, on time or they get all grumpy and bent out of shape, that’s a different route altogether. And on Sunday too! Who knew it was possible to get out of bed before the sun was up?

The weekday edition of the TH was published in the afternoon, so I did the deliveries after school. The papers had to be delivered by 5 p.m. which was usually no problem until I got cast as Tom Sawyer in a school musical.

Paper Jammed

Rehearsals started at four o’clock. School let out at three o’clock. I had Route 8, which was not terribly long and was basically restricted to just one street, Dewey Avenue, but it was a long way from Galena Middle School. I really had to haul ass on my bike to get to the TH drop-off point, complete my route, then pedal (all uphill) back to school in time for rehearsals, for which I would arrive sweaty and exhausted, but ready to suffer for my art.

The real Tom Sawyer would have found someone else to do that route for him. I tried to find someone to cover for me, but after my sub didn’t show up one day, I learned that I couldn’t count on my fellow paper carriers to help me out in a jam. That incident earned me a complaint letter from a disgruntled customer.

Get Home Pay

The problem with the newspaper delivery game was that you were essentially an independent contractor. You were in business for your tween-aged self. Each carrier was billed for their bundles every week and it was up to them to collect payment from their customers. The TH got paid either way.

I was not very diligent about collecting, and my customers were even less diligent about paying. When I did collect though, I usually had a big zippered vinyl envelope full of quarters, and even though my route was not close to home, it was close to Maggie’s Pool Hall and the video games that beckoned from within. I think it’s fair to say that my ‘take home pay’ was reduced to my ‘get home pay.’ Ha!

I wasn’t a Paper Boy for long. Just a few months really. As summer approached, I couldn’t imagine taking time out of my busy schedule at the swimming pool to deliver papers for no money. I quit that gig gladly and left the route for some other enterprising young sucker. It would not be the last time I delivered papers though.

The Orange Blossom Special

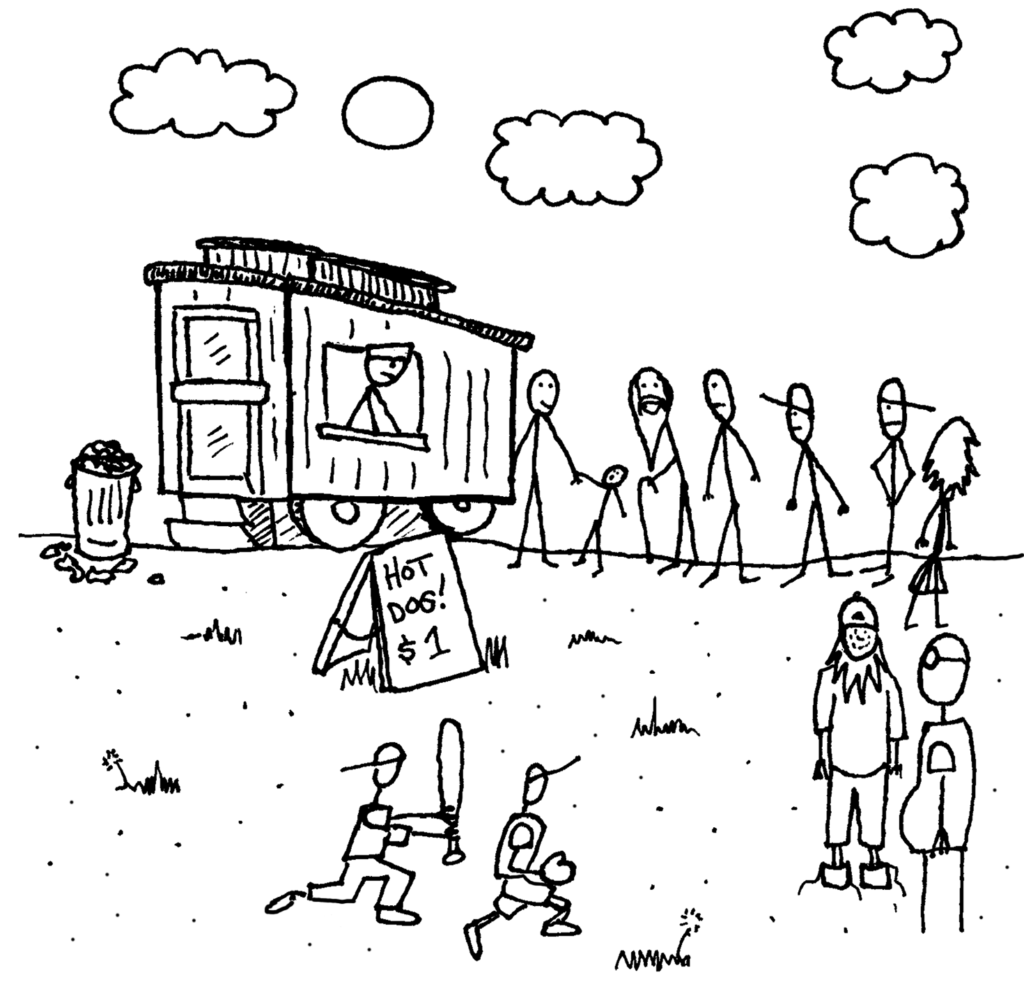

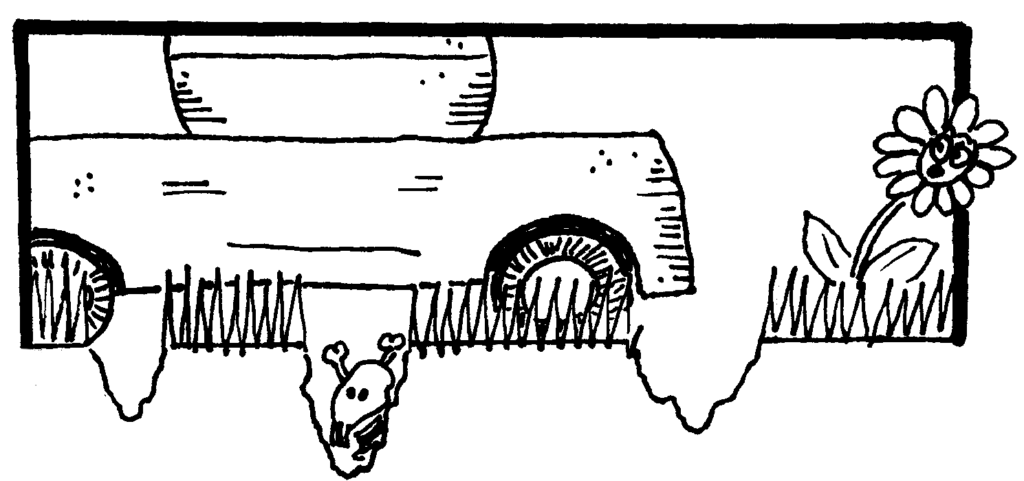

In the mid-eighties, for reasons the rest of my family may never fully understand, my Dad bought a portable (that is to say on wheels) concession stand. This was pre-Ebay, of course, so I imagine he found it through the printed classifieds.

The concession stand was located somewhere in Iowa and I went with him to pick it up. At the time of purchase, this giant monstrosity was called “The Orange Blossom Special” and was painted accordingly. The previous owners had tricked it out to look like a caboose and it was towed by a funky, orange, 1960s Ford pickup truck.

My Dad repainted the O.B.S. a more reserved auburn color, rebuilt the inside, rechristened it the “Galena Concession Company” and towed it around to various auctions, fairs, and other get-togethers where bumpkins congregate to do whatever it is we do at such things. Along with my sister, we sold hot dogs, BBQ pork, ice cream, and Auman’s Root Beer, (yes, Auman’s Root Beer—that’s another story).

The pay was pretty good; four bucks an hour when the minimum wage was three thirty-five. The idea was that my sister and I would use our individual earnings for college and the overall profits would also go to our college fund.

Not much profit was generated, however. I did get to spend a lot of weekends killing flies at tractor pulls and gorging on hot dogs. I could put away six or seven in a day easy. The hot dogs were pretty tasty too. Steamed buns are the key to good dogs. Get a bun steamer if you’re going to sell hot dogs.

Drug Dealer

Yeah, I sold drugs, but I wasn’t a kingpin. I was just a runner. Small fry. Chump change. I was a clerk and stock/errand boy at Clingman’s Pharmacy on Main Street in Galena.

This is the first job I had for any significant length of time. Two years of my life I gave to that drugstore. It was a cake job, really. I remember almost every responsibility I had there like it was yesterday. It was only two hours after school, 4 to 6 p.m., Monday through Thursday, Friday was 4 to 8 p.m., Saturday was nine to five and Sunday was 7:30 to noon, but only every other Sunday. That seems like a lot and I remember once working twenty-one days straight, but two-hour shifts I can handle.

Saturdays

Saturdays I would arrive at nine sharp, grab a broom, sweep the front sidewalk, wind out the awning, wash the windows, filter the ashtrays in the store (you could smoke anywhere you damn well pleased back then and there was always an ashtray right there for you no matter where you were), then head to the back room to do the magazine and newspaper returns.

By this time it was about eleven o’clock and it started getting a little busy so I would help out on the register and stock shelves between customers or break down boxes. Noon and it was home for lunch for an hour then back to work the register until five o’clock. Deliveries were the best because I did them on foot so they ate up the clock and I could listen to my headphones while carrying those prescriptions of sugar pills and Depends adult diapers to leaky octogenarians.

I got paid a “student wage” which ended up being three fifteen an hour. I got a ten-cent raise after a year and I still didn’t make minimum wage. That doesn’t seem right or even legal thinking back on it now… Hmmmm. Always the sucker. Always.

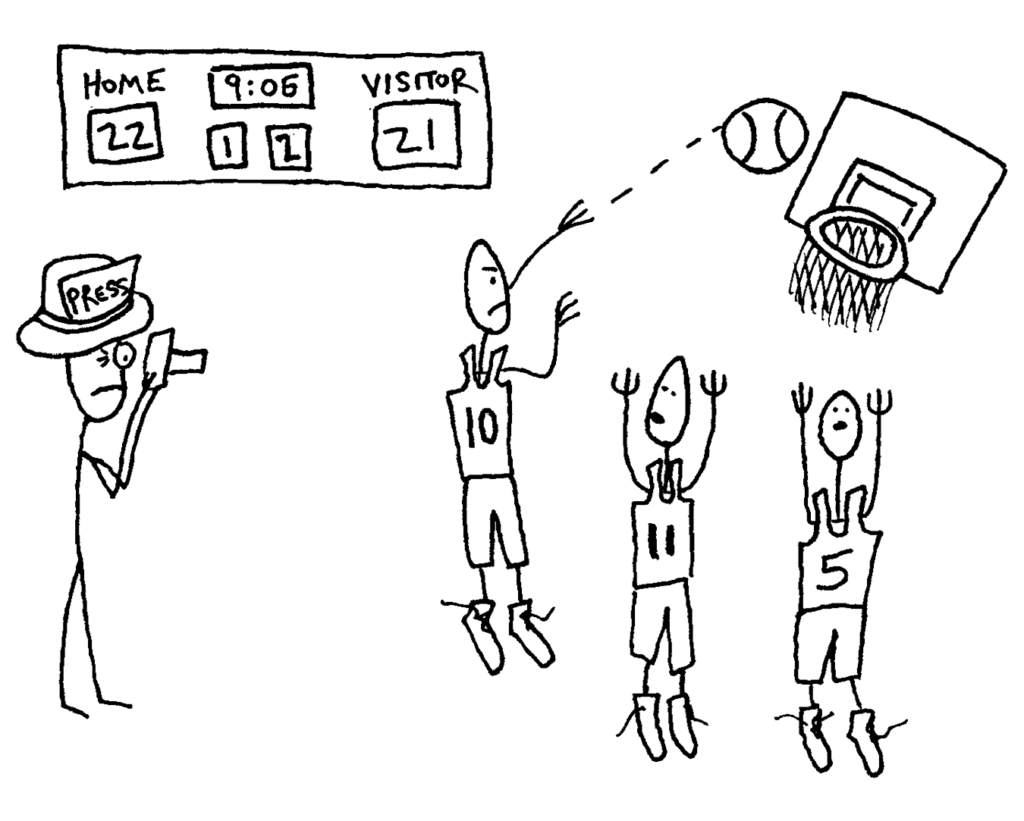

The Stringer

When I was maybe sixteen or seventeen, my high school guidance counselor recommended me for a job with the local paper, The Galena Gazette. She must have heard that I had spent some time in the newspaper business (see “The Paper Route” above).

My job was to cover the high school varsity and junior varsity basketball teams. I had to attend the home games, take a few pictures with the Gazette’s 35mm camera, talk to the coach afterward, and then write up the thrilling, white-knuckled, edge-of-your-seat print version.

It was actually pretty easy since Coach Herrig basically wrote the story himself verbally. He laid down the outline of the game, complemented the other team and their coach, name-checked a few of our key players, tossed out a stat or two along with some worn-out sports clichés, and boom! Done.

At three dollars per photo and fifteen cents per column inch, I was able to make an extra five or six dollars a week. That might have been pretty good money for a stringer in 1936, but in 1986, not so much.

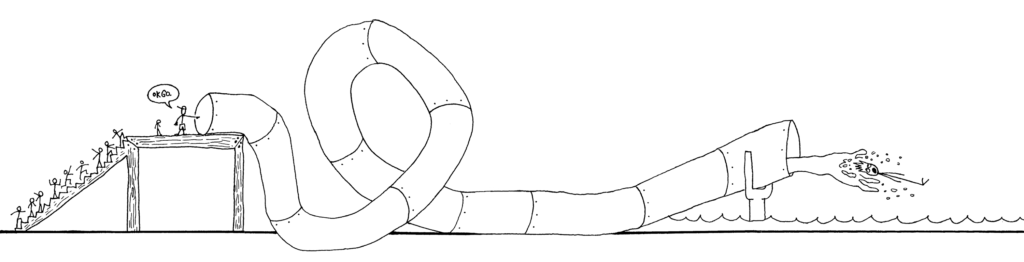

The Lifeguard

Lifeguarding has always been viewed as a very glamorous occupation. Case in point: Hasselhoff. What could be better than spending your days relaxing in the sun, scoping out the girls in their bathing suits, and just basically being a stud?

I’ll admit, from about age eight to thirteen, I was a bona fide pool rat. I lived at the public pool. I was there all day every day and frequently went back at night. It was thee place to be in the summertime and with a season pass, paid for by the parents, that shit was free to a kid. You just rolled up your suit in a towel, fastened it under your banana seat with a bungee cord, and then it was a mile (almost all downhill) to the Galena Public Pool at Recreation Park.

Learning to Crawl

During this time, I also spent my weekday mornings at the pool taking swimming lessons. My sister too. From fifth through eighth grades, we spent every weekday morning in June learning how to swim.

You wouldn’t think it would take that long, considering that we already knew how to swim to begin with, but that was the drill. I went from Beginner Swimmer to Intermediate to Advanced to Lifeguard. We learned the American crawl, the Australian crawl, the backstroke, the breaststroke, the butterfly stroke, the side stroke, first aid, CPR, how to disrobe in water, how to rescue a struggling victim – all that stuff.

In the morning in early June, when the air was still a bit nippy and the water was downright frigid, that’s what we did.

After putting in all those hours, every summer, year after year, when they built the new Alice T. Virtue Memorial Pool a quarter mile away from the now abandoned municipal pool (which was now looking downright bombed-out in comparison), I figured it was time to make my training as a lifeguard pay out.

Substitute Walking Guard

I wasn’t much of a physical specimen to behold — I was probably five foot one inch and weighed a hundred and five pounds soaking wet. I wouldn’t have been able to rescue Mitch “Baywatch” Buccanan’s bicep or one of CJ’s fake breasts to save my own life. But that was OK. I was a Walking Guard, kind of a backup to the seated gods and goddesses that looked down upon the pool waters from their glistening towers.

As a Walking Guard (and not even that, but a Substitute Walking Guard) I patrolled the changing rooms, made sure people showered before entering the pool, told kids to “Walk! Don’t run!” over and over and over again, stood at the top of the water slide and said. “Go. OK go. OK go.” over and over to kids after the previous one had safely shot out the bottom end.

I actually had to kick a gaggle of girls out of the pool for repeatedly defying the one-at-time policy on the water slide. I signaled to another guard at the bottom to give them the boot. It felt bad but there was a price to pay for not respecting my authority, as those young ladies found out.

Kiddie Pool

Raking the sand and cleaning out the kiddie pool are the other duties I can remember performing in those two days that I was a Substitute Walking Guard at the Alice T. Virtue Memorial Pool at Recreation Park.

I was never called back to sub again. Was this because they never needed another substitute guard the entire summer? Was I fired without being informed? Or was it because my five foot one, one hundred and five pound, fifteen-year-old physique was deemed too non-capable of saving any human over three feet tall? That seems the more likely scenario. I did put a band-aid on a kid’s knee during my brief career. I’m not saying that I saved this kid’s life but this basic medical procedure possibly staved off a life-threatening infection.

Oh well, this would not be the first time my four years of education in a particular field of study did not lead to gainful employment in said field.

Lawnmower Boy

I wasn’t allowed to mow our own lawn. My Mom thought that our hilly, knolly, sink-holey backyard was too dangerous. I did, however, mow a stranger’s lawn here or there.

They weren’t really strangers, I mean, I wasn’t trying to shake anyone down. (“Looks like your lawn got mowed, pal, that’ll be five bucks.”) They knew I was going to mow their lawns. I just don’t remember their names.

One lawn I mowed was all the way across town. It was just a little patch of grass that probably took ten or fifteen minutes to mow. The hard part was loading and unloading the lawnmower from the trunk of the ‘78 Chevy Malibu (the car my Dad got for me and my sister to destroy).

The house whose lawn I was to mow belonged to a local real estate agent. It didn’t seem like anyone actually lived there, yet there was no ‘For Sale’ sign on the property. At any rate, the grass had to be cut.

My Dad set the deal up and the real estate agent told him that this gig, which paid five dollars, was so easy it was like walking down the street and finding five bucks on the ground. I thought a more apt analogy was, walking down the street, unloading a push mower from the trunk of a car, mowing a slightly sloping lawn (almost every lawn in Galena involves a hill of some degree), awkwardly reloading the mower into the trunk, and then finding five bucks on the ground. But that was just my lawn mower’s perspective on the situation.

Food Service is Your Future

As high school graduation neared, so did summer, and so did college. I realized—or was made to realize by certain parental indicators—that working fifteen to twenty hours a week at the drug store and mowing the occasional lawn just wasn’t going to cut it anymore (pun intended, I suppose).

So a month or two before graduation, I entered into what would be a long love/hate (but mostly hate) relationship with the restaurant industry.

Once I took this fateful first step, it would lead down a slippery slope of culinary and hospitality work that would give me the opportunity to (in no particular order) wash dishes, prep food, work a grill, sauté, bake, make pizzas, bus tables, scrub pots, wait tables, manage, cashier, make sandwiches, boil live lobsters, sweep floors, mop floors, and (my favorite) haul stinking, leaking, impossibly heavy bags of garbage to stinky, leaking, impossibly heavy dumpsters.

I would also take phone orders, mix drinks, do deliveries, pack food, scrape pans, laugh, cry, sweat, bleed, chain smoke, vomit, (did I say cry?), throw my back out, get food poisoning, meet some very ‘interesting’ people, cut off small parts of my fingers, burn large sections of my skin and deep fat fry all kinds of things including a ballpoint pen that flew out of my shirt pocket and plunged into a fryer full of 450-degree oil, landing just out of reach of the longest set of tongs available.

These tales of woe shall be saved for the next issue.

Read the Next Chapter of Book of Jobs

Read the Book of Jobs Part 2.